Barriers in Mexico send scientists abroad - lack of resources, corruption prevent them from advancing in their work

Mexican scientists and researchers are forced to seek employment and career development abroad due to a lack of infrastructure and resources as well as government corruption that prevent them from advancing in their work, say Mexican academics based in the United States .

One hub for Mexican expats is the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, where dozens are involved in projects such as aeronautics, biotechnology and renewable energy at both Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ( MIT).

The United States is the most popular destination for both professionals and students in scientific fields seeking opportunities outside Mexico and there are an estimated 11,000 Mexicans with doctoral level qualifications who currently live and work in the country.

A 2013 Boston University study found that at least one-third of all Mexicans with a doctoral level degree live in the U.S.

Many say they choose to stay long term because of government bureaucracy and corruption back home that limit the availability of resources essential to their work.

One form of corruption that has been identified is the allocation of funds via scholarships.

The National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt) awards most scholarships for science-related studies with money allocated directly to students rather than through universities.

One U.S.-based Mexican academic believes the process leads to the inequitable distribution of funds, often leaving out those who deserve them most. But attempts to change the system have been met by resistance.

“The leaders of Conacyt want to maintain discretion over whom those funds are granted to,” said Marco Muñoz, a director in the Office of Global Initiatives at MIT.

“Scholarships are not always awarded on academic merit but because of influence.”

Muñoz also stated that financial support for Mexican scientists from the private sector is lacking.

One of his responsibilities is to find philanthropic partners to help fund scholarships for international students to study at MIT but he finds Mexico a particularly difficult country to find backers.

“The reason that I most frequently hear is ‘I don’t want to give a scholarship to students who go abroad because they don’t come back,’” Muñoz said.

He also stated that when graduates do return to Mexico they don’t always feel welcome, which he attributes to a lack of connection between authorities that award scholarships and students who have received them.

That leads to scientists being unaware of opportunities in their field and authorities not knowing what infrastructure and equipment graduates need to fully develop their ideas and research, he asserted.

Another Mexican academic in Massachusetts, Ramón Sánchez — a program director in the School of Public Health at the University of Harvard — is convinced that corruption is the biggest barrier to keeping Mexican academic talent at home.

“In Mexico, anyone can be the rector of a university just by being a friend of the governor,” he declared.

Another pertinent case is that of 28-year-old Guillermo Ulises Ruiz-Esparza, currently one of the youngest academics working in the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology Program.

He completed a doctorate in nanotechnology and biomedicine in the U.S. and is certain that he would not have achieved as much had he remained in Mexico. Consequently, he did not hesitate to return when offered a job there.

“In Mexico, with the exception of my mentor, nobody took me seriously. Before my doctoral thesis was widely publicized people told me that I was a fool, a kid. Ironically, here in the United States, Harvard believed in me and invited me to work with them. It was a dream come true and I didn’t think twice about accepting.”

He also remembers the frustration he felt when trying to progress with his work in Mexico after he had completed his doctorate.

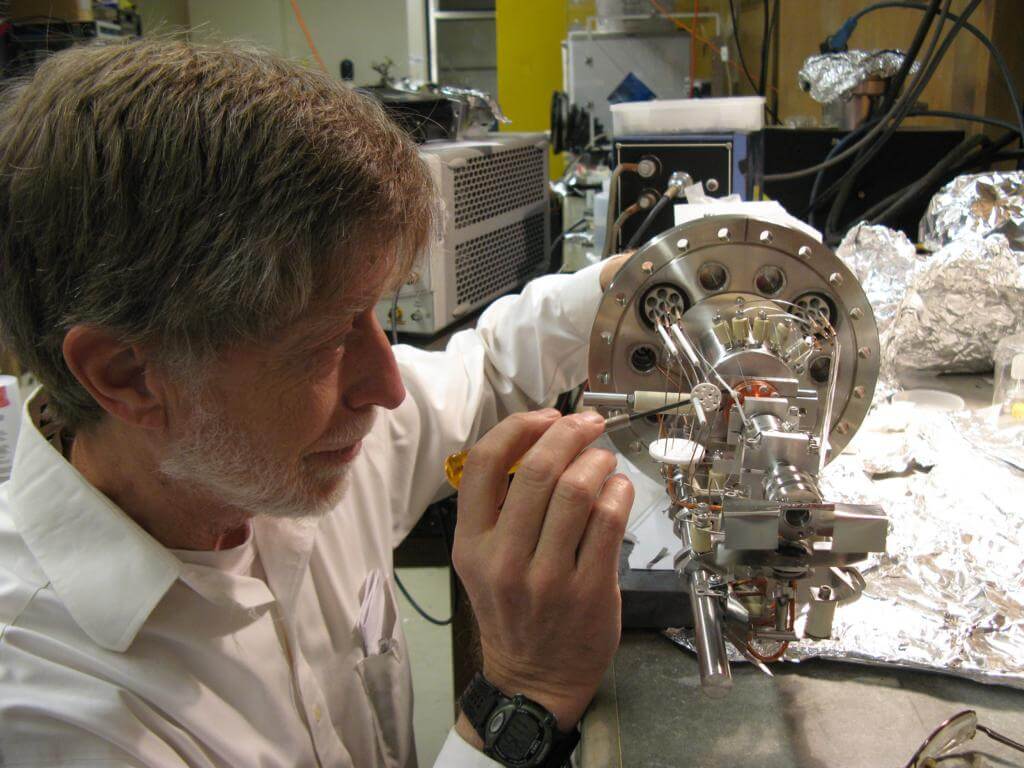

“It took five months talking to different laboratories in the country to try to do some analyses. Something that would take me five minutes to do [here] within the same building, took me months in Mexico. It’s impossible to compete with scientists in the first world when there are no resources at hand.”

Ruiz-Esparza fears that changes to U.S. immigration policies and a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) could force him and other Mexican researchers in the U.S. to return to Mexico, which would adversely affect his work.

“It’s practically impossible to do there what we do here. Highly sophisticated equipment is needed that isn’t always available in Mexico.”

Mexican academics are among the lowest paid in the world, another factor that undoubtedly contributes to the brain drain.